Forts, snakes, and Marvi: A trip to Umerkot

Written by Manahil Bandukwala

Umar-Marvi, a story popularized by Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai that is very close to Sindhi’s hearts, is recited at shrines between the prayers of isha and fajr, late in the night.

During the 12th century, Umar Soomro ruled over Thar. In the village of Maleer, Marvi was born to shephard and farmer. As she grew up she became well-known for her beauty, and infatuated a farm boy in the village. He asked for her hand in marriage, which infuriated her father and caused him to marry Marvi off to another man, Khetsen. Fuming with jealousy, the farm boy went to find Umar Soomro and gave him lavish descriptions of Marvi’s beauty. The ruler was impressed and wanted Marvi for himself.

With the help of the farm boy, Umar disguised himself and went to Maleer to find her. Coincidentally, Marvi was going to the well to get some water, and their eyes met. Taken away by her beauty, he approached her as a thirsty traveller. As Marvi came near to him, he took her on his camel and rode to Umerkot.

At Umerkot, Marvi was enticed with jewels, luxurious food, status and clothes. Umar praised her, declared his love for her, and tried to win her over, however she resisted all the luxuries and promises he presented to her. For Marvi, the soil she came from was more important than any extravagance Umar could provide. Umar was infuriated and imprisoned her in his palace. She entered deeper into her sorrow, would count the seasons, and would imagine the lives of her kin in the village. She refused to change into royal garments, and remained strong in her resolve. Umar tried to convince her by saying that although she pined for her people in the village, they had not yet even sent any message, therefore it would be best to forget them. Marvi told him that even if she were to die here, she would like her body to be sent to her people to be buried on her native soil.

The story then takes an interesting and humorous twist. Umar remained exasperated, however one day a nurse tells him that Marvi and him had had the same wet nurse, which in a way made them brother and sister. Umar was horrified at what he had done, took Marvi back to her village, and begged her parents for forgiveness. Her husband Khetsen and the village remained suspicious of Marvi’s chastity, as she had been with Umar for so long. Upon hearing this, Umar arrived at the village and in order to prove the truth Umar and Marvi underwent a trial. An iron rod was put in the fire and held to Marvi’s palm, which remained unscathed and proved her chastity. Umar did the same. Everyone was convinced of their chastity and Marvi and Khetsen lived happily.

Marvi’s resistance and the events that follow eventually convinced Umar to let her go back to her people. Umerkot, the place where Umar had taken Marvi to, is six hours east of Karachi and sits on the border of the Thar Desert. This was where we headed as the next part of our research trip.

At some point during our journey, our driver – a tech-savvy man with wireless earphones who was following Google Maps – took a wrong turn. We woke up from the bumps on the road and found ourselves in the middle of a field, with cotton plants on one side and banana trees on the other. This was apparently supposed to be a short-cut to divert us back to the highway, however a fruit truck was driving towards us, and we had to reverse our way through the dirt paths to reach the highway. After this slight detour, we soon reached Umerkot.

We met our local guides, Ramesh Maghani and Ramesh Farmar. Not only did they share the same name, they were practically brothers and both very passionate about showing us their city. The Rameshes took us to sites around Umerkot and a jogi community in the Tharparkar Desert. The story of Umar-Marvi is a key part of Umerkot’s history and culture. Marvi is a symbol of resilience here and throughout Sindh. Illustrations of scenes from the story, as well as from Bhittai’s other works, decorated the hotel we stayed at.

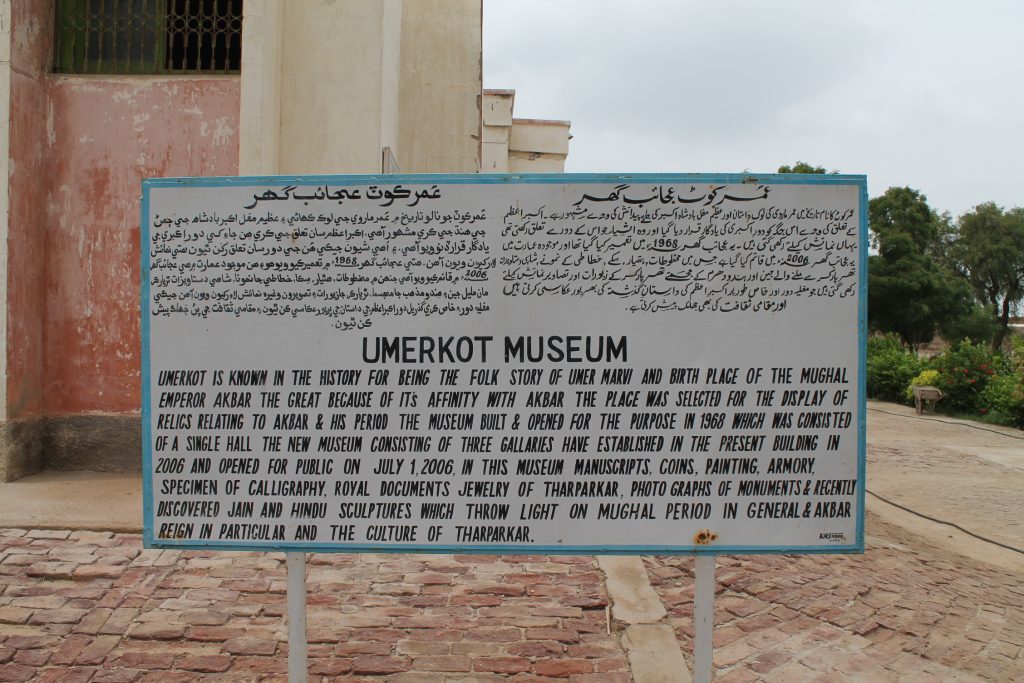

The name “Umerkot” comes from the story of Umar-Marvi, with “kot” being the four walls in which Umar kept Marvi. Ramesh M. told us that before the city became Umerkot, it was called Amarkot, after the Hindu founder of the city, Amar Singh. Amar Singh built the city’s fort, but as the story of Umar-Marvi spread around the area, the fort and city came to be known as Umerkot. The Hindu history of the city was evident in its population, which Ramesh M. informed us was currently 51% Hindu. In 1965 the areas population had been 80% Hindu and 20% Muslim (an interesting Dawn article discusses how the wars in 1965 and 1971 effected Umerkot). The Umerkot Museum showcased Hindu statues of Lakshmi, Vishnu, Naranya, Ram, and Lachman alongside Islamic texts like “An Account of the Life of Hazrat Ali” by Amir Muhammad.

Umerkot Fort had been built during the Soomro dynasty between 1026 and 1356. It had been the birthplace of Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1542, when the Hindu Raja of the time had given Akbar’s father, Humayun, refuge. We climbed its sand stone steps under the afternoon sun, using our dupattas to shield our eyes. At the top, a local musician played an accordion like instrument, as we took in the bird’s eye view of Umerkot and the Thar desert that sprawled around. The inside of the fort was sealed off to visitors, but the Soomros would have had a clear view of any invaders coming into the city.

We learnt that the Thari people, live on both sides of the border between Pakistan and India. “Pakistan’s Thar and India’s Thar (Rajhastan) are the same. My nana’s family is from Rajhasthan – I came from that side. There’s the line in the middle, but we’re all the same,” said Ramesh F.

Our next stop was a brief drive to the outskirts of Umerkot, in the Thar Desert. We met a jogi community clad in bright orange clothes and metal earrings. Jogis are traditionally a wandering community of snake charmers, even though the community we met had settled on that land. Their name derives from the Sanskrit word “yog,” meaning “ibadat ki tayari” – preparation of worship. They play a wind instrument called the been, made from a dried kadoo (gourd) connected to a reed pipe. We spoke with Misri Jogi about the work that jogis do. They performed for us, starting with a rendition of “Lal Meri Pat,” a popular song throughout Pakistan about the Sufi saint, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. In a later song, the jogis opened up straw baskets, and out came cobras that they had caught in Islamabad. The cobras swayed to the music of the been.

Misri Jogi described the relationship between the jogi, the snake, and the music as “love between the jogi’s been and the snake. When there is been played in the house, the snake doesn’t harm us. When the winter comes, we take the snake and hold it in our laps. When the been’s sound comes, the snake dances.” The jogis would catch the snakes and worked to tame them for several months, after which they would let the snakes go.

Misri Jogi started playing the been at twelve. His father used to play it, and passed the tradition down to his son. This is how the music, the method of catching snakes, the clothes the jogis wear are passed down.

This is our family work. We are a jogi community. We have these gold earrings in our ears, our orange turban, our been, and our snakes. This isn’t a new thing. It is an old way – who knows how many centuries have passed that we have been doing this work.” Children grow up hearing the been and seeing how snakes interact with the music.

Misri Jogi

To conclude our trip to Umerkot, Ramesh F. showed us a park he had recently been built. We were surprised and impressed to see a lush green park in the middle of the desert, tastefully designed with sculptures, paths, and benches. When they started making the park, they had to figure out how to level the reth (sand) and bhit (mounds). Currently, the park had a Ferris wheel and miniature zoo, and Ramesh F. told us of plans to add Dodgem cars in next. He mentioned how the idea had come to him while sitting on the beach and contemplating what he can do for the people of Umerkot. People would often not leave their homes due to the intense heat of the city, and would get bored. The park would be a place that provided calm, cooler air, and social opportunities. People from neighbouring areas like Mirpur Khas and Tando Adam come to visit during festivals, and during the monsoon season it was usually bursting with people.

He showed us how the park was run entirely by solar energy, including the amusement park rides. In general, while travelling around interior Sindh, we noticed many solar panels atop shops and homes. He told us that the Sukkur Electric Power Company was too far and expensive for locals, whereas purchasing a solar panel that run a light and a fan cost Rs. 7000 (Approximately $60 CAD). People there understood the practicality and sense behind tapping the immense potential for solar power in a region that receives constant sun. In Bhit Shah, we had also seen simple dwellings with air conditioners that were run using larger solar panel systems. Our trip to the park and conversation with Ramesh reminded us of the vast possibilities of the desert.

During our visit to Umerkot, we saw how the folk story of Umar-Marvi continues to keeps an ancient site remembered and visited. We understood the value that jogis place on past values and traditions to keep their identity strong. Finally, we witnessed the significant role that Sindhi Hindus such as Ramesh have played and continue to play in Sindh.