Archeology Meets Folklore: The Story of Sasui-Punhoon

Written by Nimra Bandukwala

Through a visit to the historical site of Bhambhore, and interviews with archeologists Dr. Asma Ibrahim and Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari, we learned about the space where evidence from the past meets the stories that continue to thrive in Sindh. Bhambhore is one of the sites of significance for the story of Sasui-Punhoon, one of the stories popularised by Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, with Bhambhore being the place where Sasui grew up.

The Story of Sasui-Punhoon

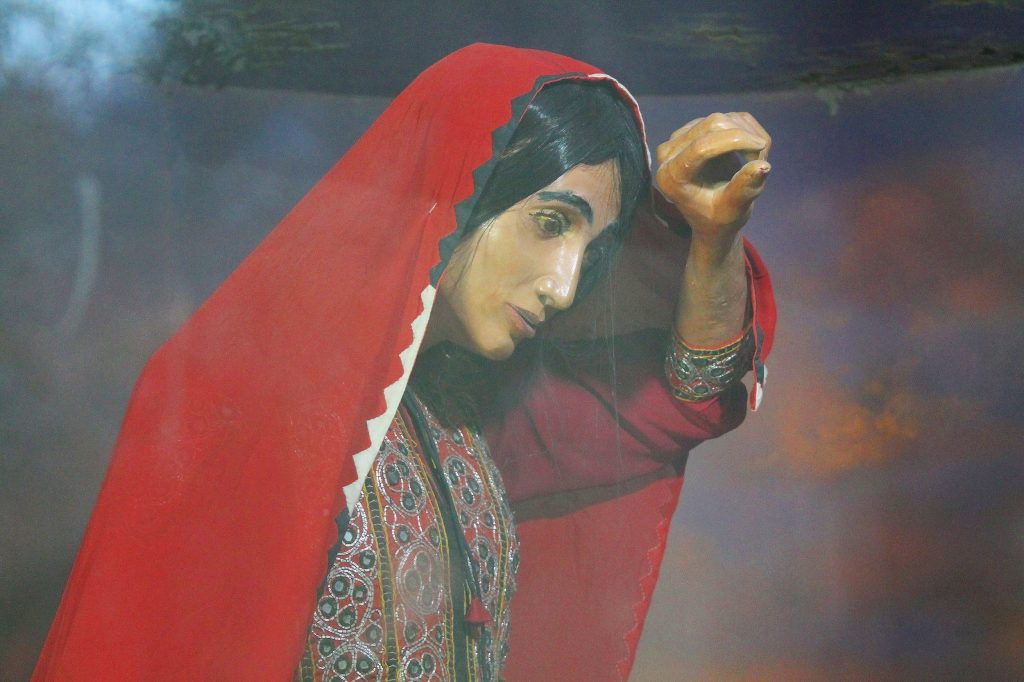

The story of Sasui-Punhoon goes as follows. Sasui was born in a Brahmin family along the banks of Bambrah canal, near Sehwan in northern Sindh. Her parents had an astrologer read her future, as was tradition in Brahmin families. The astrologer predicted Sasui would marry a Muslim, which was unacceptable to her father. He put the baby Sasui in a wooden box and sent her down the Sindhu River, now the River Indus, which flows from the mountains in northern Pakistan through Punjab and ends at the Arabian Sea in Sindh. The box reached Bhambhore, a village one hour east of what is now Karachi. Bhambhore was then a dhobi ghat, a village based on washing, dying, and drying of cloth. The village people found the box and brought it their chief, Mohammad, who adopted the baby and named her Sasui. She grew up to be very beautiful, and was known as the most beautiful girl in Bhambhore.

Bhambore sat along the trade route through Thatta. News of Sasui’s beauty reached Punhoon, the prince of Kech Makran (a desert area of the Balochistan coast west of Sindh.) He went to Bhambhore under the guise of a trader, and when he and Sasui saw each other, they fell in love. He stayed in Bhambore, working as a dhobi. Although Sasui’s father did not initially approve of the match, the two eventually got married.

Meanwhile, Punhoon’s brothers tried to dissuade him and take him back home to Kech Makran. Their persuasion did not work, so they intoxicated Punhoon until he passed out while Sasui was asleep, and then carried him away. When Sasui woke up the next day and saw what had happened, her grief grew and she was determined to find her beloved.

Historian Richard Burton provides a translation of some of the verses of the Shah Jo Risalo in his book Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus. Here is the moment when Sasui wakes to discover Punhoon missing, after his brothers have kidnapped him.

At dawn Sasui looks round, but her lover is not on the couch beside her;

Richard Burton

She searches, yet finds not the camels of her brothers-in-law at the place where they alighted;

Stooping to the ground, she gazes, and recognizes the fresh footsteps of her Punhu.

Then she weeps tears of blood, as if sprinkling the hills (over which her husband was travelling);

Crying, ‘Alas! Alas!’ she scatters the red gulal (dupatta) over her head.

How shall her wounded heart survive the loss of him, whom the Balochis have torn away from her?

Sasui began an exceedingly difficult journey towards Kech Makran through the scorching days and bitter cold nights through the mountains and land. Burton’s translation of the hardships Sasui faced are as follows:

Go not forth to the wild, O Sasui, where snakes lurk in the beds of the mountain streams,

Richard Burton

Where jackals, wolves, baboons, and bears sit in parties;

Where black vipers, in the fiumaras, oppose your way through their hissings;

Fierce hornets haunt the hills, Korars utter their cry.

And Luhars, winding round the trees swing and sway.

After which dangers, appear the sheds, – Punhu’s village-home.

Wandering in search of her love, she reached the Pub Mountain in Balochistan and fell to the ground. She managed to reach Mahabur Canal, and a spring miraculously came out of the ground. Weak and tired, she asked a passing shepherd if he had seen a caravan pass from there. The shepherd saw her beauty and that she was alone, and tried making advances on her, so she ran and prayed for help. A hill broke into two and she took refuge in it, but a piece of her clothing got stuck on a rock. The shepherd returned and was shocked to see this miracle. He repented and became the caretaker of Sasui’s grave in what is now Lasbela in Balochistan.

In Kech Makran, Punhoon became restless and melancholic while his health became poor. His father finally agreed to let him go with his brothers and find Sasui. As they reached Mabuhur Canal he saw the fresh grave and assumed it must be of a saint. The shepherd related its story to him, and realising that it must be the grave of an ardent lover, Punhoon prayed that he would also be able to reunite with his beloved. The hill parted and Punhoon and Sasui reunited in eternity. Burton translates this moment as:

Separation is now removed, and the friends have met to part no more,

Richard Burton

The souls of those true lovers are steeped in bliss, and the rose is at last restored to the rose bed.

Two Archaeological Interpretations of Folklore

We headed to Bhambhore, about an hour west of Karachi. As we walked through the ruins, the severity of the landscape dawned upon us. The scorching sands, sun beating down through our flimsy dupattas, flies buzzing around. A local pointed out the river where Sasui had arrived as a baby in the box. Her arrival, he said, brought prosperity to the dhobi ghat. Our two-hour walk through archaeological village site was gruelling in the afternoon heat, and we returned to our car tired, thirsty, and grateful for A.C. How Sasui could walk from here to Balochistan, at least a five hour journey by car today, without food or water or any idea of how far she had to go was astounding. The air of the past whispered through the architectural ruins.

Soon after our trip, we met with Dr. Asma Ibrahim, an archaeologist who had worked for several years in the conservation of the heritage site Bhambhore, as well as numerous other sites around Pakistan. She shared her experience about how folklore was always the starting point of exploration and finding a site.

She also shared skepticism regarding stories, as her approach was scientific, and stories were often romanticised. For example, people would assign the mosque of Mohammad Bin Qasim, a Muslim invader from the 7th century, as any site they wished. Another time she shared how her team walked for miles to a site in interior Sindh that the locals claimed to be Hazrat Ali’s foot. When they reached the site, there was not much over there, nor did the story fit in with the facts. Stories like these had limited historic or physical evidence, and were not useful for archeologists. However, 80% of the time the stories helped her and her team find actual sites.

According to Dr. Asma, although folklore is not given as much weight in archeology, it is important in conservation efforts as it inspires the locals to cherish and look after the site. She gave an example of how dacoits often looted graveyards in search gold. However the moment they were given historical, cultural and social significance through stories of that person, people looked after the site and ensured it was safe.

Sindhi folktales often mention place: from the ruling dynasties at the time to where the characters were born to where they grew up to where their graves are. Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari, an archeologist and historian whom we interviewed, explained how excavating these sites gives some proof that the people in these stories actually existed. When researching an area, archeologists sit with and talk to the local elders.

I then put in a conscious effort as a decision regarding what I wanted to study, what I wanted to know, and consciously began wondering if this is folk tradition (rawaayat), could these characters be real? Did they even exist or not? What was the probability that this happened or not? Whether these characters really existed or they were just part of legend? When I began thinking in this way, I began checking those facts. We were in a position to check these facts. How? Because we were people from the field of archaeology. We worked in the fields. So then I consciously chose to work with Shah Sahib’s poetry on the field. So when I surveyed the landscape, I realized that when Shah Sahib was naming places, he was charting a specific land route. There was something else to the stories that was making them stronger, and was bringing them closer to reality. Weather, terrain, the roughness of the terrain, all these things I walked and saw. The presence of their graves. So I learnt that this was a situation.

Then getting up from here and going to Balochistan. In Kech (Makran), Punhu’s qila is famous. The same father’s name, the same characters name is presented in poetry and is being said there, therefore my interests went towards this. Then I thought, could I assign a period to this story? Yes it can. When I worked in the excavations at Bhambore, I wondered that if historical evidence could be present, then we can find out that the city was plundered because of Sasui’s presense. What we saw in the excavations was that the city was cut off economically. The period is the same. Things are matching up.

Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari

According to Dr. Kaleemullah, Sindhi folktales are distinctive from the folktales of the north because they do not focus on supernatural or metaphysical elements. Instead, they mention events and incidents that could actually have happened. We know where the people in the stories were born, where they lived, where they died, and the dynasties that ruled at the time. “If we look at Bhambore, we see that those people who cleaned, and dyed clothes – they brought an extraordinary prosperity to that town,” which matches the events of the story of Sasui-Punhoon. Having seen the sites and landscapes mentioned in the story of Sasui-Punhoon, Dr. Kaleemullah said the story is very believable. We asked him about the end, where the hill swallows up Sasui and Punhoon, as this has an element of the fantastical. However, he described the landforms of Lasbela, where Sasui’s grave is, and said it had very high ridges with steep, thin drops. When Sasui was running from the shepherd who wanted to take advantage of her, she easily could have slipped and fallen in the ridge. “If you see the landscape you would have no problem believing this,” said Dr. Kaleemullah.

Whether the stories we collected were fact or fiction was certainly interesting to think about. Researchers, historians and locals held differing views. However over the course of our project, and after hearing multiple variants of the same story, we realised that as the lens we had adopted was folklore, it did not matter whether every piece of the story could be proved or not. We are interested in how the story has evolved to what it currently is, and what that means to people. Folklore has the advantage of transgressing the issue of fact vs. fiction that arises with history, religion, or archeology. Folk stories are allowed to be multiple, overlapping, and contradicting, as the reality that they present is of a plural, collective memory. This is the reason why the version told by an expert in the field was just as valid as the story shared by a villager in interior Sindh. Each persons narrative was just as valuable and valid as the next, as there was no right or wrong story, and no authority to decides this.

This experience and realisation during our fieldwork helped us to better understand the reality of the phrase “History is written by the victors.” If history is a distilled collection of stories that was handpicked and filtered by those who had power, then folklore is a pool of abundant and overlapping remembered pasts from the common person. Does that then make folklore a truer, more relevant version of history?