Saints and Folklore: Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai

Written by Nimra Bandukwala

When we first started out research into Sindhi folklore, it did not take long for Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s name to come up. This famous Sufi saint was intricately tied up with the folklore of Sindh, in particular the stories of seven women who have become know as the Seven Queens of Bhittai. It was without hesitation that we decided to visit Bhit Shah, a three-hour drive out of Karachi, to learn more about the legacy of this 18th century Sufi saint and the stories he told. Although this article discusses Shah Abdul Latif’s life and the Sindh he grew up in, you can read more about our visit to Bhit Shah here.

The Sindh of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai

To undersand why Bhittai’s work had such a powerful appeal in Sindh, it is crucial to first examine the 18th century Sindh that Bhittai was born into. The largest cities in Sindh today, Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur are a more recent development, and the Sindh of the 18th century consisted of towns and villages dotted along the shifting Indus River. H.T. Sorley, in his book “Shah Abdul Latif of Bhit” describes Sindh as follows: “The land has produced no conquerors. The people as a whole have always been peaceful and industrious, fully occupied by local affairs in the Lower Indus Valley.” At the time, Mughal power was weakening and Kalhora power (a local tribe) was rising. The British had established the East India Trading Company and had started exerting more control over the people of Sindh through taxes.

Sindh was predominantly Muslim at the time, however Islam had only been around for a few hundred years. The more ancient Hindu and Vedic practices and superstitions were still very much a part of the indigenous Sindhi peoples lives. Sindh had only had limited Arab influence in he 700s through the invasion of the Arab commander Mohammad Bin Qasim, however Islam had been brought there through Central Asia in the 12th century rather than the Arab world. Therefore the influence on Sindhi folklore, culture, and tradition, and the flavour of Islam practiced in Sindh had been mostly Indian influenced rather than Persian or Arab influences.

This is important to understand and consider when looking at Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s mass appeal and his connection to Sindhi folklore. His poetry is written within the tradition of Islamic mysticism, however because he used the language, the folklore, and the music of those indigenous to Sindh (both Muslim and Hindu) he was able to bypass the religious barrier and appeal to the wider audience of the common person. When we travelled in Sindh, we heard women, children, and men alike recite his verses by heart.

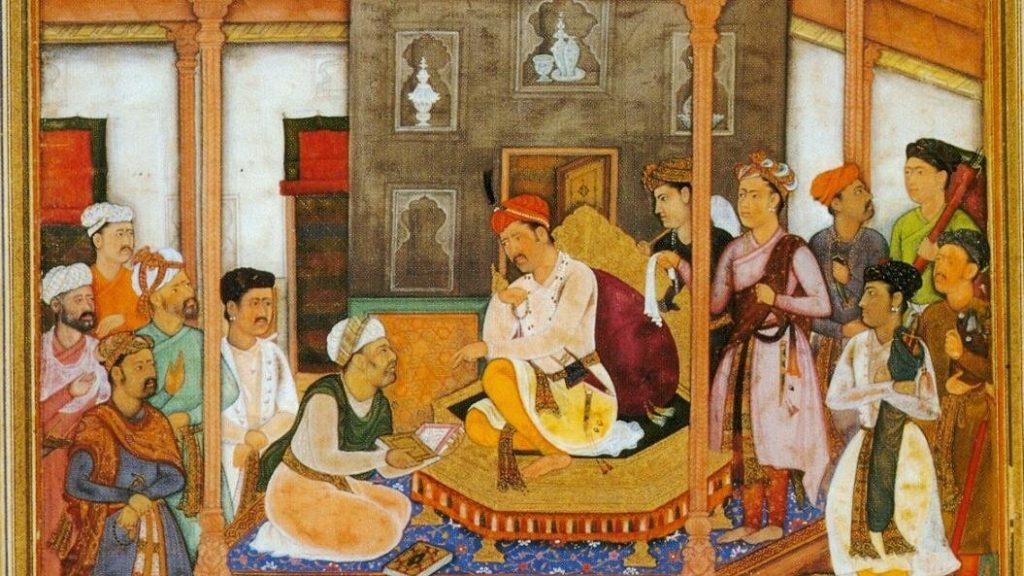

At a time poetry was primarily written in Persian or Urdu, composed within Mughal courts, and intended for an educated, elite class. What Shah Abdul Latif was doing with using the Sindhi language is an artistic way, incorporating popular folklore and stories into his poetry, and having traditional instruments accompanying his poetry was revolutionary at the time as he managed to reach the simple-minded, agricultural-based people of Sindh.

Bhittai’s Life

Shah Abdul Bhittai was born in a privileged class, yet he chose to live a simple life of abstinence. Even today, his walking stick, his begging bowl made of coconut husk, and his turban are in Bhit Shah.

Bhittai was born in Hala Haveli (today in ruins). He grew up watching the shift of power from the Mughals to the local Kalhora dynasty, yet did not get too involved in the politics of the time. He would recite his poetry and towards the end of his life hundreds would gather around to listen to his spell-binding works. He spoke about the injustices committed by the Muslims against the Prophet Muhammad’s family during the Battle of Karbala and had intended to make a pilgrimage to Karbala at the end of his life. However, his followers begged him not to abandon them and he chose not to go.

Shah Abdul Latif was married but had no heir. This must have been puzzling for many, which is why this story (whether true or created) has been told to explain why Bhittai had no children. Shah Abdul Latif’s wife was pregnant and one day she craved a certain type of fish, and her maid sent one of Bhittai’s fakirs (followers) to go find it. Learning about this, Bhittai said, “When the embryo is such trouble to my fakirs, what will the full-blown adult be? May such a blossom be nipped in the bud!” (Sorely) As a result, the child was said to have been still-born and Bhittai therefore had no heir. This story is very telling about the nature of folklore, as a way to fill a knowledge gap with meaning and understanding.

Sorley describes Bhittai’s stages in life, “from poet to sage to finally sainthood.” When he was older, he founded a village called Bhit. The town of Bhit Shah still sings his songs from sunset to sunrise.

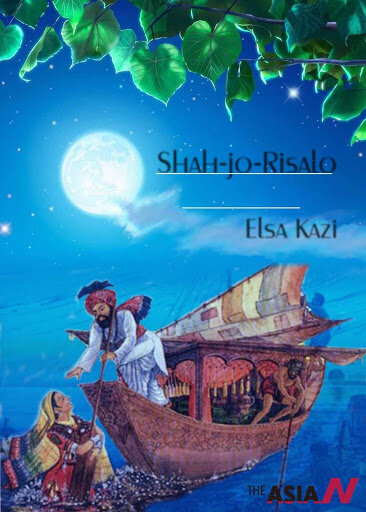

The Oral Tradition & The Shah Jo Risalo

Bhittai’s poetry was not meant to be penned. In fact, it is said that during his life he had only ever recited and had never written down any of his poetry. The poetry was intended to be sung accompanied by musical instruments. His poetry expressed the themes of wonder, beauty, the oneness and union of man with the divine, and unity of experience.

His work was said to have later been scribed, edited, and compiled by his followers (with much resemblance to the way the Quran was never written down by the Prophet Muhammad himself, but only after his death). Bhittai has been described as the first person to use the Sindhi language in an imaginative way to express emotion and story.

His poetry certainly carried some influences from Persian mystics such as Jalaluddin Rumi, whose seminal work Masnawi was almost always in Bhittai’s hand. Bhittai’s poetry falls in the realm of mysticism, which Sorley describes as an emotional attitude towards God or the divine. Through mysticism one is able to see beauty and truth in a way that cannot be seen by the rational mind. Some of the cravings of a mystic spirit include to be a wanderer, to find consolation in union, and to reach perfection. Shah Abdul Latif’s poetry uses story as metaphor to capture these elements. For example, in the story of Sasui-Punhoon, he captures this mystical craving through exploring the dangers of journeying. The wandering Sassui longs to be reunited and achieve mystical union with Punhoon.

Bhittai’s seminal work is the Shah Jo Risalo, which is a compilation of poetry that includes 30 surs (or verses). These surs are sung as Ragas or Raginis, accompanied by music. Some of Bhittai’s most popular surs use the stories of women in folktales from Sindh to share the Sufi ideas around unity and beauty. The folktales included are those of Moomal-Rano, Sassui-Punhoon, Umar-Marvi, Leela-Chanesar, Noori-Jam Tamachi, Sohni-Meher (also known as Sohni-Mahiwal) and Sorath-Rai Diyach. All of these individual stories are well remembered in the region. As any Sindhi and they will recount the dukh (pain) of Marvi, the relentless Sohni, and the the humble Noori.

Whether these centuries old folktales are alive because of Bhittai’s poetry, or whether they are just as much a part of Sindh as the desert sand is uncertain. However Bhittai did give a vehicle through his poetry to not only hear the story, but to experience through song and imaginative language, the longing, pain, and love that the women in the stories experienced.

One thought on “Saints and Folklore: Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai”

Comments are closed.