From Kolachi to Karachi: Folklore and Origin stories

Written by Manahil Bandukwala

Growing up in Karachi, we saw the presence of the city’s origin in the Mai Kolachi Bypass, a road that runs across Chinna Creek and connects where we lived in Clifton to the beach. Or in Kolachi, a popular restaurant by the seaside where we ate with the salty breeze cooling a hot paratha. Then the British came and Kolachi became “Kurrachee” and finally the Karachi we know today. While researching origin stories, we wanted to find out more about this bustling metropolis that has built its own identity today of “Karachiites” and “Karachiwalas.”

Mai Kolachi

The most common etymology for Karachi is that it comes from the the word “Kolachi.” The story goes that Mai Kolachi was a woman who settled in the fishing village of Kolachi in the 1700s in what is now Manora island. She was a member of the Kolachi tribe, the Balochi inhabitants of the village. The exact story varies from storyteller to storyteller, but each version centres the strength of Mai Kolachi. Some versions say that she lost her husband in a storm and went looking for him, despite the dangers present, as is depicted in the short stop-motion film, “Kolachi’s Story,” released by Matteela Films. Others say that she lost one of her sons to a crocodile attack, and her other son, Moriro, killed that crocodile. Mai Kolachi subsequently became the head of the village.

During our trip to Bhit Shah, we visited the Bhit Shah Museum and saw a diorama of the famous fisherwoman on the shore of Kolachi. We learnt that Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai had elaborated on the story of Mai Kolachi in the Shah Jo Risalo, and we talked to the caretaker, Mohammad Kamal Kori, about Bhittai’s version of the story.

And this is your city, Karachi. In this village the men go off on their boats, in the waves, to catch fish. The mothers and sisters of the village would sit by the seashore for months waiting for the men to return. They come for maybe a night or two, then go back to sea. So what these women go through, their emotions, their reality, this is what Shah Sahib shares in his poetry.

Now the village of Kolachi slowly became Karachi. The men who went out on boats would go wherever the wind blew them. When the wind blew them back, they’d come back. Sometimes it would take a year, other times it would be two. There was this worry. The women wouldn’t know how the men were doing, when they would return. There was no way to communicate with them. Shah Sahib has given words and meaning to these worries of restlessness and unease. He is saying that to deal with the constant worry that they must – “parwardigar us fikar mai raazi hai” – trust in God.

Translated from Urdu

In all of these iterations of the story, Karachi’s origin comes from the bravery and resilience of a woman dealing with the unknown. We asked archaeologist, Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari about his interpretation of the story as well. He said that the Kolachi we know of did not exist prior to 18th century. “It was not a port, but a village of Kolachi caste people, who are a Baloch sub caste.” He said that “The story of Mai Kolachi is a story from the much more recent past. It is not a very authentic story – it is need based. If someone comes and asks, what is Karachi? They immediately created a connection that this is what it is. But as such, in asaasi literature, there is no mention of this.” Mai Kolachi presented a heroic tale for people to attach meaning to the city’s origin, so people stuck to it. This made us reflect upon other stories that we had heard, such as the fort we had visited where Umer kept Marvi locked up in Umerkot, or the grave of Noori Jam Tamachi in Kenjhar Lake, and how many of these stories can oftentimes act as important anchors to a community, providing both meaning and belonging. In the case of Kolachi, it is impossible to trace whether the story is true, partially created, or entirely fiction. However the theme of resilience is one that continues to drift through the air, and can be felt wherever you are in the city today.

Moriro ain Mangarmachh

Dr. Lashari then recounted other stories from the area of Kolachi, including the 11th century folktale, “Moriro ain Mangarmachh,” where a fisherman kills a vicious sea monster.

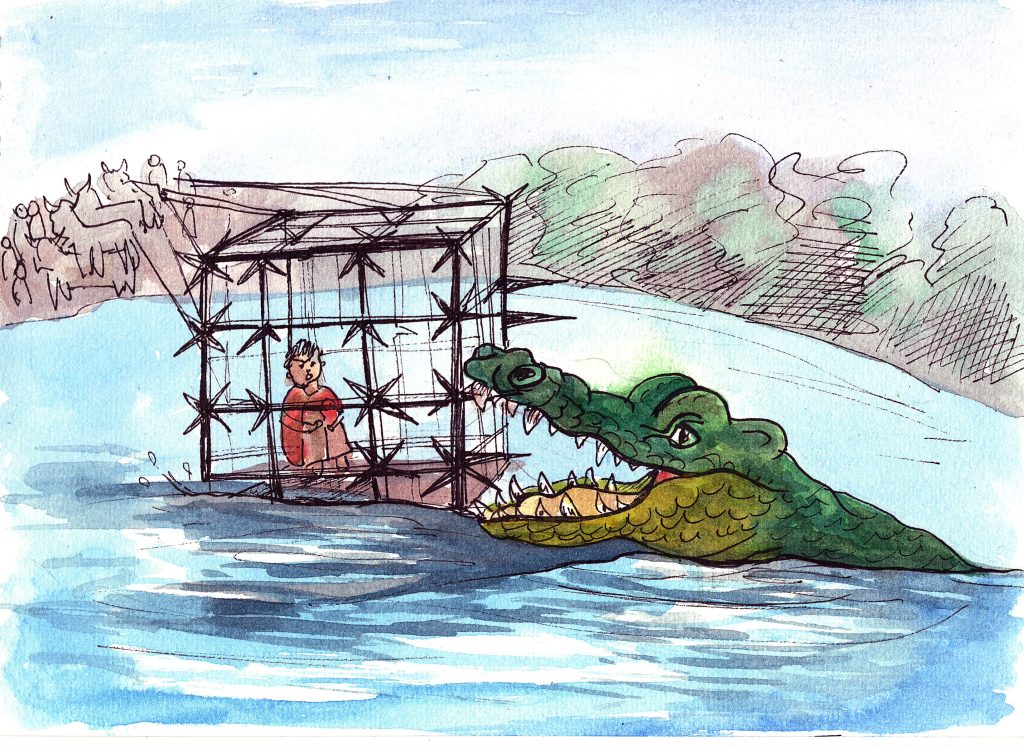

The story goes that in the area that is now Clifton, was a dangerous whirlpool called “Kalachi jo Kun.” A sea monster settled in this vortex and would swallow passing boats. In some versions the creature appears as a crocodile, in others a whale. What remains certain is its massive size and strength. In a village nearby lived seven brothers. All were healthy and well-built, except Moriro who was shorter and had a handicap. Although they were a fisherman family, Moriro did not join his brothers during their journeys at sea. Once, the brothers did not return home, as they had tragically been caught in the whirlpool and swallowed by the sea monster.

Moriro resolved to take revenge against this monster that had devoured his family. He had an elaborate iron cage built with spikes and sturdy ropes. These were fastened to buffaloes, and the cage was lowered into the water. Moriro sat in the cage and the villagers were to pull it out when he shook its ropes. As expected, the creature was enticed into the trap, caught, and pulled up. Its stomach was opened to retrieve the remains of the brothers. They were buried nearby and Moriro spent the rest of his life as the keeper of the grave. This grave still exists in Karachi tucked away at Gulbai Chowk. Read more about the grave on The Karachi Walla’s blog.

It is interesting to note that elements of this story are combined with Mai Kolachi’s story (i.e. stories that claim that Moriro was Mai Kolachi’s son), however it is very probable that two separate stories have been linked together over time. Dr. Kaleemullah’s suggests that the vivid details and facts present in this story demonstrate that the story could have taken place.

In this story you find lots of detail – the metal cage, the levers that you put in and pull which causes a blade to emerge. The mechanics of the story are very possible because it is easy to do. Just as they are explaining it, it is possible to understand. Ropes are used and tied, the story tells us how many layers were tied and how 60 bulls were attached. There is paraphernalia…the details vividly create a picture to show that these are not just stories. If it were just a story a lot of aspects would be fictionalised and added, for example the characters muscles would be stronger, they would fly. However over here, they did not bring in explanations like these. They are talking only about actual physics. This is very interesting.

Dr Kaleemullah Lashari, translated from Urdu to English

Whether the stories of Mai Kolachi and Moriro took place or were created out of the necessity to add intrigue to Karachi’s history, will remain unknown. However the variability of version, characters and place reminded us that Karachi, like many other cities that have become large metropolises in the span of a century, is a city that keep reinventing itself, that is in search for a meaning of its own.

One thought on “From Kolachi to Karachi: Folklore and Origin stories”

Comments are closed.